June F. Becker, O.S.B., Ph.D.

is Director of Psychological Services at St. Meinrad College and School of Theology, in Indiana.

Human Development -Volume 10, Number 1, Spring 1989, pp. 5-10

He was throwing another tantrum. I put my arms around him to hold him immobile until he calmed down enough to listen. I explained to him that Jeff needed space, too, that we all need to get out and have a variety of friends, that Jeff still liked him but couldn’t spend all of his time with just him. I told him that I like him, too, and that he’s a very likeable kid, even when Jeff is not around. He started to cry, much to my surprise, and said that he was afraid none of the other kids would like him and that was why he stayed so close to Jeff. I hugged him tighter and asked him why he thought that way.”

This counselee is not speaking of an actual biological offspring; he is a celibate with no children of his own. This child he describes is an “inner child,” a part of his personality that has become unmanageable. By imaging, or personifying, a part of himself, this counselee is using a currently popular method of self-discovery that is helpful in professional counselling and spiritual direction. Although this method is no cure-all for every personality problem, its usefulness in encouraging self-acceptance merits attention.

UNRESOLVED ISSUES PERSONIFIED

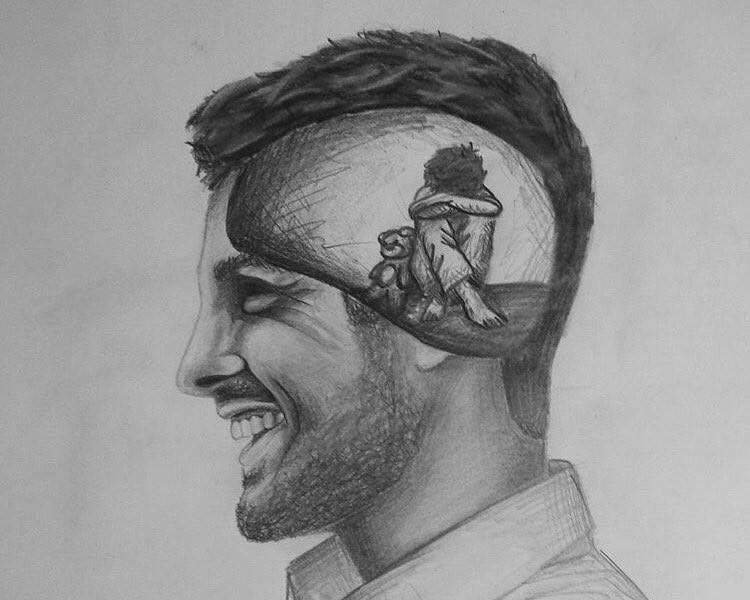

The inner child is a personification of one’s feelings, perceptions, and behavioural reactions that developed in early childhood but were never integrated with the more mature feelings, perceptions, and behaviours developed later in life. Although one grows in wisdom and understanding, and thus comes to more adult ways of responding to life situations, one can often experience oneself reacting as though one had learned nothing new in twenty, forty, or even sixty years.

For example, one remains fearful of authority figures even when they are peers. Or one becomes shy before audiences in spite of repeated successes. Earlier fears, resentments, inferiority feelings, and misperceptions remain ingrained in one’s reactions, split off from later learning as though two people lived inside the skin, one an adult and the other the child from the past.

Students of human behaviour are sometimes put off by seemingly unsophisticated references to an imaginary figure inside the person. Psychology has been criticized for “personifying” emotional dynamics, turning the operations of the psyche into little people—-id, ego, anima, shadow. There is practical value, however, in anthropomorphizing one’s inner dynamics. In Re-visioning Psychology, Jungian analyst James Hillman explains that such images are needed because conflicting emotions act like autonomous persons. They are far more like characters in fiction than like elements in physics. One can understand much more about these dynamics by envisioning each as a person having an independent interior existence motivated by personal intentions. These concrete personifications provide substance for what would otherwise remain abstract and vague.

The inner child carries wounds not yet healed, unresolved feelings, unfinished business

Even after agreeing to imagine a “child inside,” one still might not care to spend much time with her or him. After all, the inner child is an embarrassing side of the personality—still “childish”— and the inner child often leads one back to events of the past that one would prefer to forget. The inner child evokes negative reactions because it is formed from issues that have not been resolved in the course of time, issues rooted in earlier painful situations. The inner child carries wounds not yet healed, unresolved feelings, unfinished business.

As a result of these wounds, psychological retardations have also developed in specific areas such as friendship, self-image, assertion, or authority, where one does not react maturely. For example, a young man may be very mature in his work context but show infantile reactions in the face of a friend’s neglecting him. Because of childhood traumas in the area of intimacy, his development has been blocked and he has not learned adult skills for coping with an occasional rejection. His inner child collapses into tears.

Ignoring this tearful child will do nothing to resolve the immaturity. The pain must be examined; the inner child listened to, the wound dressed. Despite initial aversions to meeting the inner child, personal growth requires that the child be faced.

A second reason for attending to the inner child rather than repressing it is that the inner child is the carrier of one’s creativity, spontaneity, affection, sexuality, and enthusiasm – qualities that first appear in childhood and that give zest to life. When the inner child is blocked from integration with the rest of the personality, these qualities remain inaccessible. Continuing to distance oneself from the child’s immaturity deprives one of this vitality. In reclaiming the shadow part of the inner child, one re-inherits life. Those who have successfully negotiated midlife will recall the burst of psychic energy that follows resolution of childhood issues.

INNER CHILD NEEDS PARENTING

The first step in meeting the inner child is to acknowledge that it exists. The second step is to go beyond thinking about it and to start communicating with it. One leaves the safety of abstract commentary on childhood issues and enters into fantasy dialogue between the inner child and “me,” that is, between the child and the adult whom “I” claim to be. My child and I begin to talk about our differences. Such “pretending” feels uncomfortable at first, but activating the whole inner child— feelings, memories, spontaneous reactions—allows the inner child to say so much more, to give more new information than would surface by merely thinking about the child.

Once one enters into dialogue with the inner child, there are positive and negative ways of interacting with it. Many people increase their troubles by trying to deal with the inner child in self-defeating ways. They try repressing, ignoring, disciplining (i.e., using “will power”), and attacking (self-criticism) this immature aspect of the personality. Such practices are just as ineffective with respect to the inner child as they are in rearing flesh-and-blood children. ,

A child’s feelings do not go away simply because the adult says that they should. An inner child is no more rational than other children. All respond to harsh corrections with procrastination, depression, or forgetfulness; they embarrass the adult with further whining and slink away to erupt again at another inopportune moment.

Ironically, one can be grateful that the inner child is not easily destroyed. Persistence on the part of the child is rooted in psychological needs that the adult self cannot recognize. In other words, the inner child serves as an alarm system. It carries a message for the adult. This message indicates the unfinished business or unmet needs that must be addressed if the person is to continue to grow psychologically. A common example is overwork. When too much of one’s time has been given to work, inspiration eventually flies out the window, self-discipline falls apart, melancholy sets in. The inner child has begun to object. It cries out for affection or for play or for whatever basic need is not being met. Wholeness will not be achieved by becoming a workaholic; the inner child lets the adult know this.

Rather than resort to child abuse at such times, the adult would do well to listen to what the inner child is saying and to explore ways of responding. One becomes a parent to oneself as one learns to provide for the inner child whatever was missing in the first, historical experience of being parented as a real child.

Good parenting of real children provides a model for how to deal with these troublesome leftovers from childhood. How would a good parent respond to a weeping or fearful or rebellious five-year-old? A regular diet of spankings and reprimands will destroy the child’s spirit. Healing the wounded inner child means becoming a nurturing parent for oneself. It means holding, listening, explaining, and protecting the inner child from destructive criticism. Positive parenting also involves patience and a realistic sense of a child’s pace, since children do not change quickly.

Admittedly, parenting also involves some firm limit setting. Children need the protection of firm but manageable boundaries. If one’s personality is a bit addictive or hysteric, then the inner child may need firmness, but most inner children err more in the direction of too much guilt. These children need more encouragement than discouragement.

IMAGE CAN BE THERAPEUTIC

Some cautions are in order. The idea of the inner child has captured the popular imagination. More and more authors are using this image, while increasing numbers of spiritual renewal centres offer workshops on it. Enthusiasm for such an intriguing image can cause one to overlook the limitations of this approach. The inner child approach is one method among many. I have found the inner child image to be a powerful tool in therapy, yet I would not introduce it to everyone; some people are more inhibited than helped by the use of fantasy. Furthermore, the method can help a person to see inner conflicts more clearly and to return to unhealed wounds, but cure does not always follow automatically. Other tools may be needed. The most useful perspective is to think of inner-child work as one sometimes-powerful tool among many. It might be helpful to summarize precisely what this approach does for the person.

The inner child has proven to be a helpful image for personal development because it provides a way of facing personality deficiencies and painful memories that would otherwise be too threatening to acknowledge. By relating to the underdeveloped aspects of one’s personality through the image of a separate person, the inner child, one can maintain sufficient objectivity or distance to “dialogue” with the problem and thus move toward resolution. The image of a fragile child also evokes the necessary compassion for oneself that one must have in order to accept personal limitations. The concept of the inner child is particularly timely today for two populations, those in midlife and adult children of alcoholics, as both groups recognize the need to return to childhood to attain full adulthood.

As the concept of the inner child grows in popularity, descriptions of the child also seem to expand. Speakers and writers on the subject work out of ‘several different schools of psychology, so in literature on the subject, the inner child is sometimes wounded, sometimes divine, sometimes shadow, sometimes real self. This proliferation of inner-child descriptions can be confusing, yet most are basically compatible with one another.

AUTHORS DEVELOP CONCEPT

W. Hugh Missildine, in 1963, first presented the image of the inner child in Your Inner Child of the Past. Missildine developed three concepts: the inner child who lives on in one’s adult life, the importance of being a parent to oneself, and the principle of mutual respect between the inner child and one’s adult self. His image is of a wounded, vulnerable child. Drawing on his clinical practice, he writes in “detail about a number of faulty parenting patterns, such as perfectionism, overindulgence, and neglect. He describes the effects of each pattern on the little child and the corrective self-parenting patterns needed later in life.

Transactional analysis was developed by Eric Berne in the 1950s and popularized in the 1960s by Thomas A. Harris in his best-selling I’m OK, You’re OK. Harris described how one’s multi-natured personality switches “ego states,” i.e., how one responds from moment to moment as an adult, a parent, or a child. The child state is constituted of one’s reactions, largely emotional, to all that was seen and heard in those early vulnerable years. This definition of child is consistent with Missildine’s, but transactional analysis adds another dimension in emphasizing the emotional resources to be gained from the inner child.

In Born to Win: Transactional Analysis with Gestalt Experiments, Muriel James and Dorothy Jongeward describe three inner children, two of whom carry a storehouse of healthy resources. The natural child is born first. This child is affectionate, curious, fun-loving, sensuous, and self-preservative. That is, by nature, one does not know the meaning of “I cannot love.” Through this child the person naturally desires learning, seeks happiness, enjoys sexual stimulation, and will do whatever he or she needs to do in defence against psychic abuse.

The little professor surfaces at about the age of ten months. This is the source of intuition and creativity. With unschooled wisdom the little professor can figure things out, including how to get one’s way with adults. The little professor can resolve many dilemmas encountered in childhood but unfortunately is often squelched by demanding adults. This is a clever child, worth listening to when searching for creative solutions to old problems.

The last inner child to evolve, according to James and Jongeward, is the adapted child. This child wanted parental approval, feared the loss of love, and as a result had to adapt to meet the demands of these giant figures. Too often the adapted child reflects the most troubled part of the personality. Some typical patterns of detrimental adaptation include compliance, withdrawal, and passive aggression. The compliant child goes along with expectations on the outside and compulsively adheres to rules but does not deal with inner anger and hurt. The withdrawn child learns passivity: don’t think, don’t feel, don’t do. Passive-aggressive children learn how to keep out of trouble, but just barely; they learn to annoy those in authority but seldom obviously enough to invoke their wrath. In the face of certain authority figures, many a healthy adult can see his or her own adapted child surface in an unexpected attack of obsequiousness, stage fright, or underhanded defiance.

JUNGIAN PSYCHOLOGY COMPATIBLE

Jungian psychology has become increasingly popular as our age has become more concerned with issues of spirituality and midlife. Talk of the inner child is very much at home in Jungian psychology. Jung himself acknowledged the creativity of his own inner small boy. In his work, Jung relied on fantasy figures such as the anima, trickster, and wise old man to describe the dynamics of the psyche. This style of speaking – personifying psychological dynamic – is typically Jungian. The methods that he recommended for encountering these characters of the unconscious are also the same methods that are being used today for meeting the inner child: dream work, active imagination, fantasy dialogues, dance, drawing, working with clay, and so forth.

What Jung adds to the conversation on the inner child is the concept of a universal or archetypal child. This is Jung’s way of indicating that the vitality and strength to be gained from the child are universal, inherent in our nature rather than personally acquired. Jung distinguished between the parts of the psyche attributable to personal history (personal inner child) and those attributable to universal human nature (archetypal child). The inner child is shaped by events in early childhood, by one’s personal history of being loved or unloved, but archetypes predate one’s personal history. Archetypes are motifs or predispositions inherited as part of the human species, as patterns of the psyche that have evolved from generation upon generation of human emotional experience. The child archetype is a very life-giving piece of this evolving psyche.

Janice Brewi and Anne Brennan discuss the value of the child archetype in their most recent book, Celebrate Mid-Life: Jungian Archetypes and Mid-Life Spirituality. They see the task of midlife as that of disengaging from one’s over identification with one’s role (persona) and coming to terms with one’s shadow. The child archetype is needed to face one’s shadow; without it, one can take one’s adult status too seriously. Through the child archetype, one can accept the more humiliating aspects of the shadow because this child is the source of simplicity, humility, and love for all creation including oneself. The child archetype also finds productive ways of reinvesting the energy that was going into maintaining the roles of the persona. It opens the midlife adult to greater consciousness through child-like activities of make-believe, play, music, art, and prayer.

Brewi and Brennan also suggest that the child archetype may be a crucial factor in healing childhood (personal inner child) wounds. At midlife, each of us must go back to make peace with the past. A universal or archetypal aspect of childhood is the ability to withstand pain and to rise again. With the strength of this inborn hopefulness difficulties can be overcome: “The child archetype incorporates our damaged child and transcends it.” We bring this archetypal hopefulness to bear by giving birth to our child again, by holding and re-parenting our child in the present.

Carol Pearson is another author writing within a Jungian framework. In The Hero Within: Six Archetypes We Live By, Pearson devotes a fascinating chapter to two child images, the innocent and the orphan. The innocent has not yet begun the journey, not yet been thrown out of the Garden of Eden. Innocents believe that everything exists to satisfy them, to take care of them and provide for them. Pearson remarks that this is natural for a small child but requires much denial and narcissism to be maintained in adulthood. Most innocents, confronted with the necessity of making their own way in life, move on to the stance of the orphan.

The orphan is the child inside who still feels the loss of early security and who still resents not being taken care of by others. Orphans are disappointed idealists. They feel powerless and abandoned. They appear angry but are profoundly fearful underneath. Like any other child, the orphan cannot be told simply to grow up and get on with the journey. Pearson discusses the difficulties of instilling enough hope in the timid orphan for him or her to give up this resentful passivity and take on the responsibilities of adulthood.

In reclaiming the shadow part of the inner child, one re-inherits life

ALCOHOLICS’ CHILDREN FIND RELEVANCE

Charles Whitfield’s Healing the Child Within: Discovery and Recovery for Adult Children of Dysfunctional Families may be the most widely read book on the inner child these days because of its appeal to adult children of alcoholics. Whitfield describes the emotional wounding of a child in a dysfunctional family, the psychology of shame and guilt, and the later grieving and recovery process. Whitfield’s use of child imagery can be confusing, however, because he uses so many terms interchangeably: child within, inner child, divine child, real self, true self, and higher self. Equating the inner” child with selfhood may give a maturity to the child that Missildine, Berne, or Jung would never accept. They would more likely say that the child represents an early natural healthiness that must be restored so that the later mature self can emerge.

ENCOUNTER THROUGH IMAGINATION

Some approaches to the inner life are more practical than theoretical. Gestalt therapists, for example, would argue that one should not theorize a priori what the inner child is like; rather, one should find out by experiential encounters with one’s own inner child. Reading others’ accounts of the inner child is stimulating, they would say, but in the end the only truly healing image is one’s very own inner child.

Almost any imaginative activity—dreaming, modelling clay, dancing— can be used to encounter the inner child. The most common method is that of guided fantasy, especially fantasized dialogue. Fantasy techniques train the participant to focus on vivid visual images and then to enter fantasy scenes where he or she interacts with figures such as the inner child. This method is already a familiar technique for prayer and reflection. Jean Gill gives some examples in Unless you Become Like a Little Child: Seeking the Inner Child in Our Spiritual Journey. She elaborates on two useful scenes from scripture, the nativity and the story of Jesus with the children. Gill also shares numerous illustrations of how she has let her inner child join her in her own prayer.

Many more leads for interaction with the child are given in James’s and Jongeward’s Born to Win: Transactional Analysis With Gestalt Experiments. Gestalt therapists tend to ask for more overt participation in the fantasies. The individual is told to “experiment,” change chairs with the imaginary figure, act out the relationship, exaggerate the movements. The dialogue that emerges is not imagined silently in one’s head but voiced aloud complete with intonations and gestures. At first, personal inhibitions may limit how freely one enters into these experiments, but practice improves one’s ability to follow where the fantasy leads.

Keeping a journal or writing about the fantasy is a common method when working without a facilitator. John Pollard provides help along this line in his Self-Parenting: The Complete Guide to Your Inner Conversations. This text is presented as a workbook. It is an introductory manual for those who prefer detailed, specific instructions. Pollard recommends daily thirty-minute dialogues with the inner child and a written account of all that the child says during these conversations. He provides a complete list of questions to ask the inner child while becoming acquainted during the first two weeks of meetings, then teaches several other exercises for later encounters: resolving inner conflicts, nurturing the inner child, building self-esteem, establishing goals, and continuing dialogue.

SOURCE OF WISDOM

Missildine quotes Walt Whitman’s poem “There Was a Child Went Forth,” which is about a child going ahead each day to become for years afterward whatever he or she looked upon that day. The concept of the inner child has also gone forth from Missildine’s consulting room and been amplified by various theoretical contexts, by new audiences, new methodologies, and new terminology. It appears that both in practice and in print the vulnerable inner child has become also the source of inner wisdom and archetypal vitality.

RECOMMENDED READING

Brewi, J., and A. Brennan. Celebrate Mid-Life: Jungian Archetypes and Mid-Life Spirituality. New York: Crossroads Books, 1988.

Gill, J. Unless You Become Like a Little Child: Seeking the Inner Child in Our Spiritual Journey. New York: Paulist Press, 1985.

James, M., and D. Jongeward. Born to Win: Transactional Analysis With Gestalt Experiments. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1971.

Missildine, W. Your Inner Child of the Past. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

Pollard, J. Self-Parenting: The Complete Guide to Your inner Conversations. Malibu, California: Generic Human Studies Publishing, 1987.