In this seventh section we shall proceed to explore the dynamics of needs that we perceive as consistent and those that we see as inconsistent, and seek some understanding of why they appear so. This may shed light on why our behaviour some times puzzles us, when we know what we should do, yet fail to do what is right. Our needs have the ability to blind us. We can think we know ourselves well and yet the inconsistencies of our lives reveal to us that there are needs at work in us that escape our awareness.

Needs and Developmental Aspects in the Human Life Cycle:

While needs are universal and therefore common to all human beings, they assume different strengths and form different dynamic patterns within each individual.

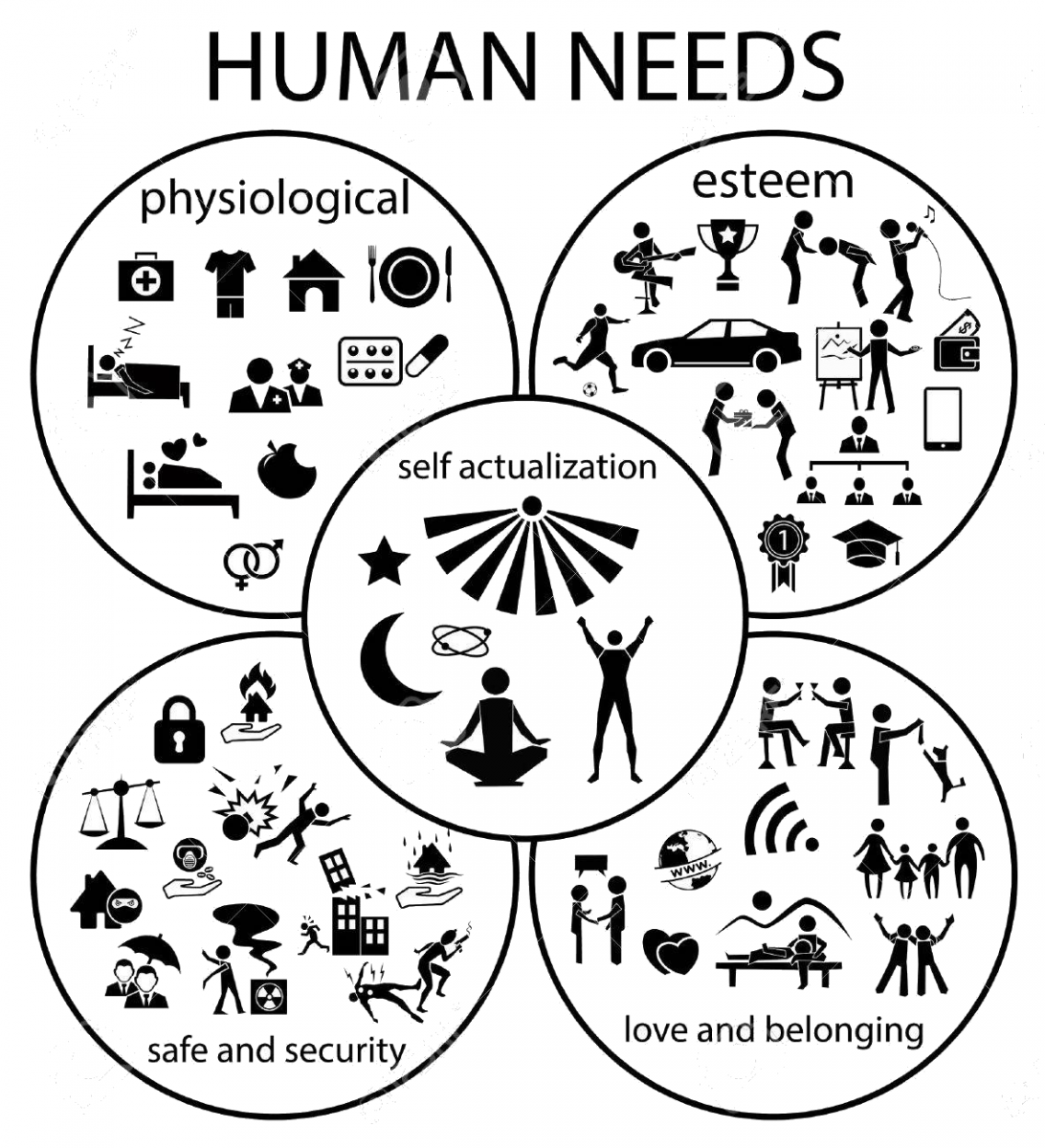

Needs in a general sense are innate tendencies to evaluation and action. An illustration of this is to evaluate and act towards people, situations and objects in terms of their importance for oneself (as in the Intuitive Appraisal we discussed earlier). They can be seen as action tendencies (as in emotions) resulting from deficits in the person, or from natural inherent potentialities seeking to be exercised. They range over different levels of the person’s psychic life, including needs that are related to the Psycho-physiological (hunger, thirst, etc), to the Psychosocial (affiliation, dependency, etc.), and to the Spiritual (knowledge, transcendence).

From a different perspective, we can relate needs to the developmental phases undergone by the person. The earliest stages of life revolve around the exercise of sensory capacities and the satisfaction of basic physiological instincts like eating and drinking. Succorance (dependency) is central in early phases of life, as a necessity for survival given an infant’s real dependence on others for safety and nourishment. As a child’s capacities grow, needs like Autonomy and Aggression emerge in its moves towards some primitive forms of self‑assertion. Childish forms of Exhibition and Recognition will also be common. Experiences of being refused, of failure, will touch needs like Abasement, Defendence, Infavoidance and Counteraction. The development of the child’s intelligence and continued exploration of his or her environment will involve other needs like Knowledge, Achievement, Domination, Change. Going to school and widening social experience will affect other social needs like Succorance, Affiliation, Submission, Domination, Nurturance, as well as touching in new ways needs like Abasement, Autonomy, Recognition, and so on.

Different experiences will create different “need‑strengths”. Extremes of deprivation or over‑gratification will lead to “hang‑ups”, blocks, fixations, or wounds. For example, too much gratification of a child’s need to be on show may increase exhibitionism in later life. Too little manifestation of affection and love may heighten succourance needs. Explicit or implicit messages from parents and others that certain needs are “bad” or unacceptable can lead to shame and anxiety becoming connected to this need. To protect one’s sense of self‑esteem, these needs and the connected feelings may be repressed. This can even happen, though unintended, when some ideal is over‑valued, for example being “strong” may be so prized by parents, that any trace of “weakness” (normal feelings of anger, hurt, wanting affection) is repressed.

Not only will the stages of personal development affect the emerging patterns of needs in each individual, the person’s cultural setting will also have an influence. The family of origin is most important in passing on and mediating cultural emphases. For example, it is said that Eastern cultures place more emphasis on dependency, especially in females. Western societies tend to encourage more autonomy. Attitudes to aggression will also differ in various cultural settings, as will accepted ways of dealing with and expressing anger.

Need Patterns

As we have commented, needs may assume a variety of dynamic patterns in the individual. The following are some possibilities:

Mutually supporting needs ‑ some needs easily reinforce each other:

- autonomy and aggression

- dominance and aggression

- abasement and infavoidance

- counteraction and achievement

These may be further supported by the low strength of other needs:

- high domination and aggression, is supported by a low need for submission

- high achievement, is supported by a low need for change and play

- high abasement and aggression, is supported by a low need for autonomy and domination (hence a rather weak person, lacking in self‑confidence, is easily depressed and frustrated)

“Conflicting” needs ‑ some needs may seem to be in conflict with each other:

- autonomy may appear to be in conflict with succorance

- aggression may appear to be in conflict with affiliation

- defendence or infavoidance may appear to be in conflict with achievement

Sometimes these conflicts may reflect differences between actual behaviour and the underlying tendencies, for example, underlying strong aggression that is controlled by outward behaviour that is very “correct” and guarded or defended. These conflicts may reflect the influence of education, or result form the process of maturity (growing up). An older sibling may learn to be both very deferent to parents (submission and/or infavoidance) and dominating with younger siblings (domination).

Often such apparent conflicts may reflect areas of conflict and compensation within the individual.

- High achievement may be a compensation for an underlying strong abasement.

- High nurturance may be a way of controlling others and satisfying domination.

- High autonomy and succorance may reflect a strong ambivalence in the person between wanting and seeking freedom, and needing to depend and cling to others.

- Nurturance and affiliation may be strong for warding off strong aggressive impulses.

Clustering of needs ‑ some needs form natural clusters related to areas of daily function;

- Work Orientation: achievement, counteraction, order, change

- Interpersonal Relationships: affiliation, nurturance, succorance, sex, aggression, autonomy, domination, exhibition.

- Self-Regard: abasement, defendence, infavoidance, achievement, recognition

- Authority and Leadership: submission, autonomy, domination, defendence.

Needs and maturity ‑ the strength (or lack of strength) of needs, and their function, in a person’s character can help or hinder their maturity and effectiveness in ministry. Here are some possibilities, related especially to need strength;

| NEED | TOO LOW | TOO HIGH |

|---|---|---|

| ABASEMENT | indicates a lack of insight into one’s weaknesses and consequent defensiveness. | it betrays a lack of self‑confidence that may lead to fatigue, sensitiveness, mistrust, depressive moods. |

| ACHIEVEMENT | if compensatory, it is self‑centred, and not for the Kingdom. | |

| AFFILIATION | may indicate superficiality or drivenness in relationships. | |

| AGGRESSION | may indicate a use of repression in coping with one’s aggressiveness. | will interfere with inner peace, community living and apostolic service. |

| AUTONOMY necessary for mature self‑reliance | can lead to difficulties in cooperating with others and in working with authority. | |

| CHANGE flexibility and renewal | can indicate rigidity and stubbornness. | may mean superficiality and restlessness. |

| DOMINATION capacity for leadership | may become an obstacle to obedience and cooperation | |

| NURTURANCE | inadequate concern for the weak and the “little ones”. | can become “mothering” or paternal controlling. |

| ORDER needed for organisation | may suggest scatteredness in thinking and haphazard, disordered living. | can suggest rigidity and become an end in itself, may be a vehicle for aggressive control of others. |

| SEX GRATIFICATION | may be repression of sexual impulses and feelings. | obvious tension; in this case, sexual need is often being used as a vehicle for another need. |

| SUBMISSION (deference) | cooperation or mature obedience may be difficult. | possibility of infantile obedience or inability to assume leadership. |

| SUCCORANCE | too much independence for community living, or a defensive closing off to receiving affection. | indicates emotional immaturity and lack of self‑reliance; can be obstacle to self‑giving in service, difficulty in chastity, clinging to affective support. |

| COUNTERACTION | may indicate a readiness to give in to difficulty or a tendency to unreliability and irresponsibility. | the person may stick at a task that has become irrelevant or useless, in a driven fashion. |

Unconscious needs at work in us can make us appear like angels but leave us hollow, lacking in freedom and full of compromise. In the next section we shall look more closely at how needs can appear to be motivating us in ways that seem to have integrity but in fact are inconsistent with the values of the Gospel.