Three Ways to Live Out Values

Religious vocation is a complex reality. As we try to live our vocation with ever deepening integrity we discover that not all our motivations are always what they seem. Even as we believe ourselves to be acting out of the highest religious and spiritual values possible to us when we make our vocational choices, we are not always aware of the ways in which those choices are influenced by social factors that require adherence to certain norms and come with a personal cost. Ongoing formation is itself a good example of this. I join religious life and persevere through many years of training and still ‘they’ want me to do more, to grow, to change. Adherence to social/religious norms can feel burdensome and generate resentment, until I discover for myself the beauty of developing my relationship with Jesus, discovering the pearl of great price that is hidden within myself, enjoy that process of adult maturity. Social psychologists have found people are highly susceptible to social influences as demonstrated by classic experiments in obedience and conformity. Why do people conform? Why, despite costs to individual liberty, do we comply with whims of groups? Or, in some cases comply with, but only to spend a great deal of energy pushing against, the group(s) we affiliate with?

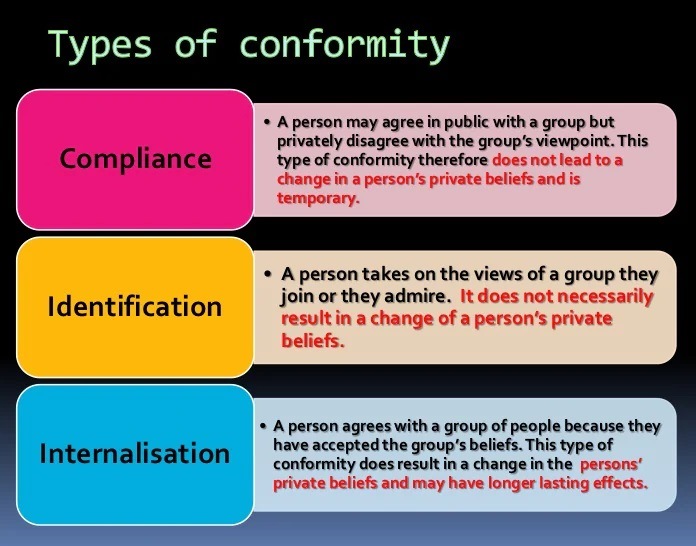

Compliance

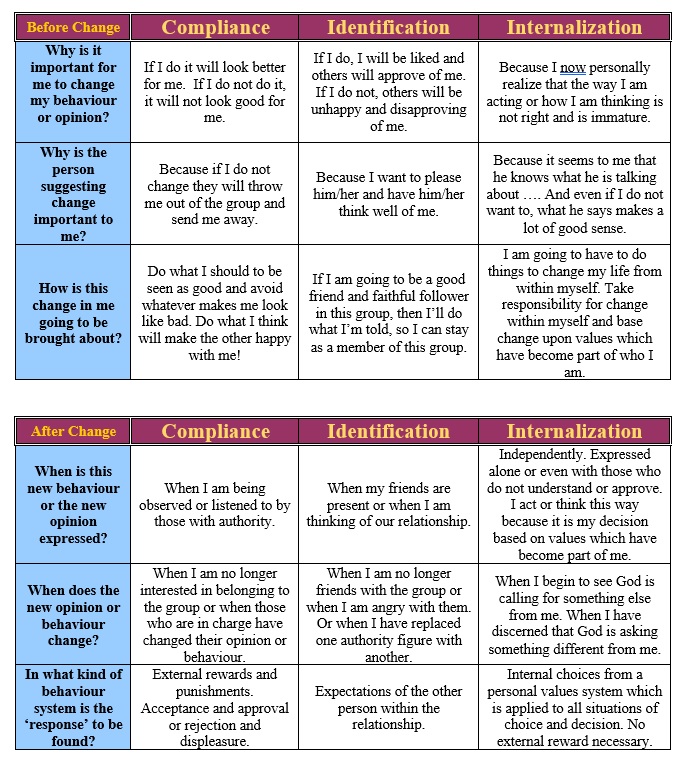

Compliance is when people appear to agree with others but actually keep their dissenting opinions private. In compliance a person accepts the influence of another person or group in the hope of reaching some goal, or avoiding some consequence, controlled by the other person or group. In compliance values are accepted because of the external forces and not because they have been freely chosen. Compliance encourages pretending; following the leader or the group; being in the group but only as an observer – watching but not really getting involved, standing back without committing oneself to anything that might call for others seeing who I really am, or what I really think, or feel. Just doing things in order to please others. Underlying motives might include fear (of rejection, of authority, of culture), expectations (or fear of clash of expectations), or perhaps shame (being sent home, made a public example, embarrassed in front of others, etc).

A driver must comply with the rules established by a statutory body responsible for safe use of roads and vehicles, in order to protect all users and ensure an orderly system of behaviour. Compliance is not always to be considered a negative influence on value-choice. We would all agree on the necessity for keeping the roads safe. However, when compliance is a compromise that results in an individual losing his or her own personal autonomy, living a duplicitous life, or sacrificing his or her own authenticity to keep the rules, then we may well begin to question the value of compliance. Unfortunately this occurs more often than we would like to think.

For what will it profit a man, if he gains the whole world and forfeits his life?

Matthew 16:26 RSVCE

Compliance in religious life results in emotionally stunted and spiritually immature individuals. While obedience is a vow we profess, the value inherent in it is not compliance, but rather a deep seeking of the will of God in one’s life. Understood properly this is a vow to be in relationship with God and to discern and seek the ways that this love can can be nourished and followed. The will of God is not to be confused with rules of obedience, though there is a well-entrenched practice of this attitude in religious life.

Compliance finds it roots in the child parent relationship. We comply with the wishes of our parents. They hold our lives in their hands. As adults we hopefully grow beyond that dependency and move towards a healthy autonomy in which we can make good decisions in the service of others, and that enable us to transcend ourselves and our own needs.

Identification

In the case of identification a person adopts new attitudes or ideals not necessarily because they are important in themselves, but because to the person they are worth identifying with; they bring a reward. A man who joins a monastery may find great comfort in himself, by identifying with the external characteristics of the monks belonging to that order. The values that the monastery holds meet the needs of the individual. So, when he adopts these values, he is able to increase his self-esteem and better the image he has of himself. He may obey the leader or follow a group because it is gratifying to his own self‑image. He is a good monk. He dresses like a monk. He acts like a monk.

In identification a person assimilates characteristics of other people or groups, as in when a person takes on the persona of another such as how they act, the things they say, or they way they dress or do their hair. Identification results in granting a high level of significance to the external signs and symbolism of belonging to a social organisation. In highly regulated organisations, individuals find personal satisfaction in symbols of acceptance and belonging, such as uniforms, and grades of achievement (such as the soldiers stripes of authority or badges of honour, academics wearing gowns and motor-boards, or different grades of religious habit adopted as a sign of progression through postulancy, novitiate, temporary vows, perpetual membership, and religious superior). The influence of identification is very strong in groups which value highly the status that comes from being affiliated with that group.

In religious life identification keeps the individual in an emotional dependency. He is motivated to conform because he is looking to be accepted, approved, validated, found to be pleasing to others, seen to be one of the group. Again, this is a place of questionable emotional maturity. There is no doubt regarding the beauty of belonging to a religious group with a rich charism and spirituality. That is a gift for the whole world. The immaturity is in the dependency on the groups approval, rather than the free living of a divinely inspired charism.

For though I am free from all men, I have made myself a slave to all, that I might win the more.

1 Corinthians 9:19 RSVCE

Internalization

Internalization indicates that a person is disposed or free to accept a particular value as leading them to self-transcendence. The individual is transformed by this value. His behaviour can be attributed to the love he has for this value and its importance to him.

In religious life and ministry we are faced with choices that must be measured against what enables us to live our lives in the most fruitful way we can. When we own our values in such a way that any negative influence of another person or group does not cause us abandon what we value, then we recognise the influence of internalization. Irenaeus said, “For the glory of God is the living man, and the life of man is the vision of God.” This is often quoted as “The glory of God is man fully alive” perhaps indicating that being fully alive is connected to the very life of God. In internalization our behaviour conforms with what brings the Glory of God, not out of fear, or desire to feel good about belonging, but because we desire God. We desire to know God and reflect God in our lives. We do not have anyone telling us to do so, nor do we do so under the influence of what is acceptable to others. Our thoughts, judgements and decision are informed by the values which are important to us. This process of internalizing values enables change within us and shifts our perceptions so that what we once saw as undesirable becomes desirable. Our motivation shifts so that we can begin to adopt what we once sought to avoid. Interiorization brings a renewed freedom.

The process from Compliance through Identification to Internalization may be summed up as a journey from Information to Formation to Transformation.

Transformation from Internalization

MSC religious life has been in a profound process of change over the last sixty or more, and at the heart of that change has been a shift from a structure that could accommodate the conformity of compliance or identification. With the changes in the Church and in society during these decades the enormous challenge has been for religious and clergy to gain a richer self-understanding, especially of the motivational dynamics at work within them. This challenge has been demanded even more in the last decade, due to the disclosure of sexual abuse by clergy and religious and the concealment of those crimes by religious institutions.

From the cries of the abused, to the ecclesial vision of Pope Francis, we are being asked to live lives of integrity and authenticity; lives of Transformation brought about by a deep internalization of the values we profess.

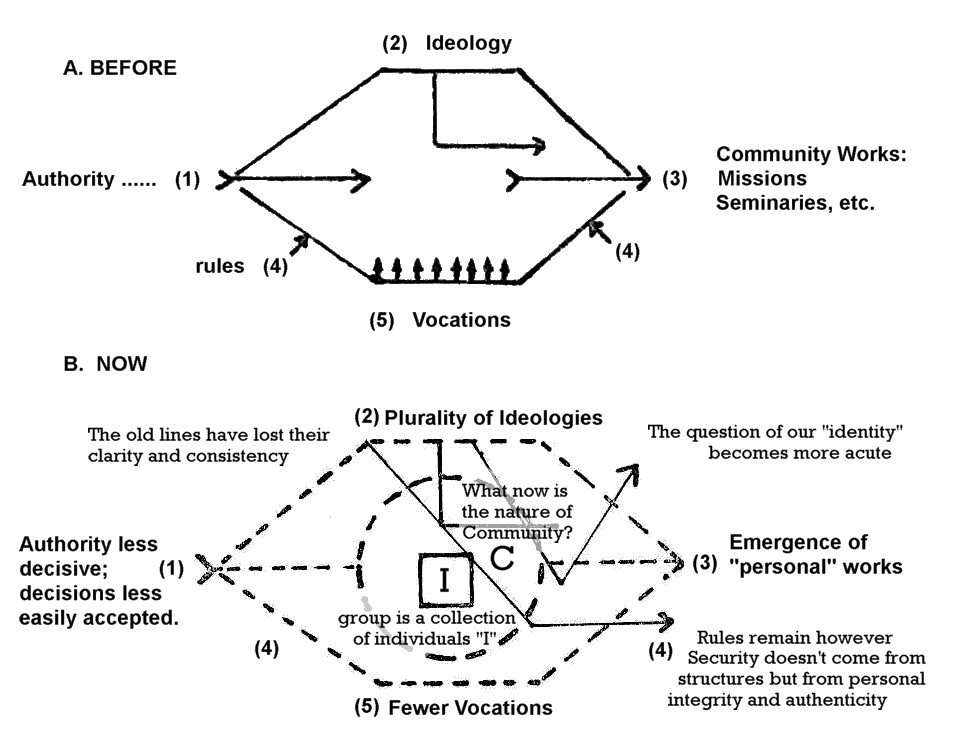

The following extract is from former Superior General, Fr. E. J. Cuskelly, MSC, seeking to help the members to understand the changes taking place across the congregation. The tectonic shifts he describes are those of a system of compliance and identification to one motivated from internalization. Perhaps what he writes in his book, A New Heart and A New Spirit (Chapter 1. p.9) is prophetic, visionary. Even though at the time it was experienced as a major diminishment, perhaps it is the sign of the Holy Spirit calling us yet again as a church to live a more mature Christian life. [I have updated the diagrams a little without changing the content].

A New Heart and A New Spirit

We have been discussing “Renewal and Adaptation” for some years now. Ideas are not lacking about what should be done; many changes have been made. However, differences of opinion frequently prevent fruitful concerted effort. Each religious group will have to seek in its own way, in line with its spirit and its history. The following considerations, I believe, can help us all to place the need for renewal in its existential context, and thereby to see the direction we should give to our work of adaptation.

NOTE: Within this framework,

a). There was no question as to “our identity”;

b). There was less questioning about “community”;

c). There was less preoccupation with THE INDIVIDUAL PERSON and his fulfilment — there was less need for it.

A. “Once upon a time” religious life was, to a certain extent, viewed in a way which can be expressed schematically as in Diagram A. It was then relatively easy for superiors to know the lines along which they should seek to unify and direct their religious institute.

- A centralized authority could make decisions and these decisions were accepted and carried out without too much difficulty.

- A common theology and ideology unified the group and helped in the common thrust towards common goals or community works.

- Community works, accepted by all as goals of the Society, were a unifying (almost identifying) force.

- Rules, common to all, gave a feeling of unity and made it relatively easy for Provincials to keep an eye on the “spiritual welfare” of individuals and communities. There were our community exercises.

- More than was usually realized in the days of plenty, the constant inflow of vocations, assuring the members of young confreres to help with and carry on their works, was a strong moral support and confirmation of the value of their own vocation. Young men were eager and adaptable, accepting willingly appointments to the works which needed them.

B. TIME OF CHANGE: The old lines have lost their clarity and consistency. New elements have entered into the diagram, old ones have disappeared.

- Authority is less decisive; its decisions less easily accepted.

- There is a plurality of ideologies, demanding different practical expressions; but IN A NUMBER THE OLD IDEOLOGY AND ITS DEMANDS REMAIN UNCHANGED. This results in bewilderment, rigidity, reaction.

NOTE: Within this WEAKENED framework,

a). The question of our “identity” becomes more acute.

b). The group appears as a collection of individuals — the “I” of the diagram. “Renewal … an excuse for doing their own thing … failure to admit in practice that the common good must be serviced before the individual ..”. The disintegrating structures give no security, so the individual seeks his personal security in his own way.

c). There is much talk about community (C) – much talk, but little agreement as to what is demanded for community. After all, what is now common to all; in what do the individuals commune?

Conscious and Unconscious Attitudes towards Change

Exercise

The following exercise creates a WordCloud of values. In the box list the five top values you consider most important to your life. What does this say to you about the values of your lived experience in the light of the statements on Compliance, Identification, and Interiorization found in the table above?

Some Further reading:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-human-beast/201904/why-people-conform