This paper was presented to the participants of the 2021 General Conference which was a hybrid conference of both online and offline sessions and work. This paper was offered to assist conference to reflect on the process of deep change through generative listening that the congregation is being invited to participate in. This participation is an active engagement in the process of the Spirituality of the Heart introduced at the 2021 General Conference. The paper was written by Chris Chaplin msc.

The June session of the 2021 General Conference was an opportunity for the leaders of the Society to connect with one another and with the significant experiences of their own leadership. We asked, “What is your lived experience of your leadership?” “What are the most connecting and life-giving experiences?” “What are the challenges and potentials at the systemic level that you don’t want?” “What allows such situations to be present?” “What is missing that does not provide leadership with the knowhow to work with such situations?”

Feedback from the break-out-groups was very clear. The first two days communicated a strong optimism and affirmation of the joy experienced by leaders even amid difficulties, limitations, and weaknesses; the centrality of mission; and the need to listen, to connect with one another, build community and a sense of belonging. It was good to also hear the importance of synodality and congregationality. This was a very positive starting place.

The responses of the third day focussed on challenges and potentials. Planning for the future; confronting realities like the pandemic, nationalism, clericalism, safeguarding, individualism, ageing, diocesan mindset; building team spirit, belonging, relationships, listening, connection, accompaniment capacity, willingness of members; the need for formation processes that form members who can and want to commit to the congregational mission. Some of these matters for consideration were specific to entities, but most were related to the congregational system, and it is the latter I would invite us to think on in terms of change.

One of the frequent themes that has come up in the conference so far is change. It was spoken of in a variety of ways and using different words; transformation, new, confront, build, plan, grow, develop, but all suggest a movement of change is not only desired but is also taking place. My friends in India have a delightful expression when I mention some problematic issue. With the wiggle of the head, they shrug their shoulders and say, “What to do?” And, indeed, what to do within our congregational system when at times it seems we are facing intractable issues and feeling inadequate in our capacity to change them in a meaningful and lasting way? So, let’s look at it a bit and what it requires.

Our relationship to change

We begin with our own relationship to change and the attitudes and feelings we hold around it. It is no surprise to you, if I say we are in a threshold era globally, not just congregationally. We have been for some time, and we know it is challenging for us to find new approaches that lead to sustainable responses, rather than leading from paradigms which no longer serve the congregational mission. You will recall Humberto’s Iceberg presentation and the need to look beneath the symptomatic level to the patterns of thinking, structures, and assumptions that lie hidden underneath our routine problems. We live in a moment of history where change is happening so fast that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing.[1] We often don’t have the time to do the necessary reflection that helps us use our authority for the highest possible outcomes and our leadership suffers as a result. We can feel left behind or disempowered. In members and leaders change stirs up varying levels of resistance which may give rise to personal or collective grief; the kind of grief that was voiced in response to the “unwillingness of members to contribute” said in different ways in the June 14 feedback. We sometimes sense the energy that is spent, the frustration and tiredness, because we didn’t do the pruning (cutting back, letting go) when we needed to, leaving greater dilemmas to be dealt with. A conference voice spoke of the loss felt by younger entities as older entities retire to die. There is always the risk of not living the present, and closing the future before it happens. We may experience insecurity at the seeming non-permanence of change, and yet change happens whether we like it or not, and paradoxically is one of the most constant realities we live with.

“Some people don’t like change, but you need to embrace change if the alternative is disaster.” [2]

Change that animates for Mission

Our relationship to change is varied. Many desire to be open to change, and to have confidence in the value of change that animates for mission. French author Victor Hugo once said, “Change your opinions, keep to your principles; change your leaves, keep intact your roots.” In the history of religious life transformation occurs when we get back to the Gospel roots. It is what motivates us to move forward despite obstacles. The Holy Father encouraged us, “remember your first love”[3], and have the “smell of the sheep”[4] on you (be among those you serve – as leaders that means with members) to help us be grounded in the realities which sustain and energize us. He reminds us, “the missionary expansion of the Church began precisely at a time of persecution”.[5] Change can feel like revolution, as if something is asking us to forego what we most value, but often change is leading us to a refinement; a more authentic living of those values.

“Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.” [6]

The Gospel challenges us to be active participants together in the change process, not passive onlookers, or isolated victims. The 2019 Korean Conference affirmed the importance of a paradigm shift towards congregationality and synodality, of accompanying, listening to the story of members not just giving directives, of mentoring not monitoring, of listening communally for the Word of God. We recognised that listening enables us to get into the life of members, sharing their fragility, joy, defensiveness, bitterness and pain. Active participation in change can empower us together, in “letting go” and “letting come” what is emerging from the Heart of Christ.

Facilitating Systemic Change

Although people are committed to change, we often find either change does not happen, or things change for a short time, and then old patterns re-emerge. This is a dilemma which confronts all organisations. Research in Fortune 500 companies in the USA suggested that more than 70% of their organisational change programmes just did not work. So, it is not only religious congregations that experience such problems, even businesses with lots of money to spend discover that this does not guarantee success.[7]

“Our dilemma is that we hate change and love it at the same time; what we really want is for things to remain the same but get better.” [8]

Research shows that at the heart of successful organisational change is a cultural shift from blame to acceptance. The work of Ronald Heifetz helps to illustrate this.

Technical Problems and Adaptive Challenges

“The adaptive context is a situation that demands a response outside your current toolkit or repertoire; it consists of a gap between aspirations and operational capacity that cannot be closed by the expertise and procedures currently in place.” [9]

Ron Heifetz, Director of the Centre for Public Leadership at Harvard University, distinguished between what he called technical problems and what he called ‘adaptive challenges’. The technical problem is one which we can solve using existing expertise – if not our own, then by bringing in experts. We could say “more of the same, but better”. This links to thinking by an organizational scientist called Gordon Lawrence who talks about the politics of salvation – the assumption that we will only be saved by a saviour from outside. If only a saviour will come and fix things everything will be solved without having to struggle with the problem ourselves. Heifetz recognised that there were some problems which could not be resolved on this basis.

These were adaptive challenges in which the very assumptions on which experts were operating were themselves part of the problem. The only possible response according to Heifetz is “Now, for something completely different!” This links to what Gordon Lawrence calls the politics of revelation. The solution is embedded in the situation, and has to be revealed. God is in what is happening now, if only we would take time to discern.

“I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to reach my destination.” [10]

It’s important to note what Heifetz says about adaptive change in terms of the need to involve all members – we named this in Korea as the process of accompaniment, and approaching the whole at the systemic level. The following section is adapted from a video transcript of Heifetz.[11]

Adaptive Challenges

You can’t organise collective enterprise above the very small group level without an authority structure. So, the practise of leadership almost always takes place within structures of authority. One either leads without authority from below, or from outside the organizational structure putting pressure on it, or one leads from an authority position. Not all people in positions of authority lead by any means, we know that, because we complain frequently about the lack of leadership we get from people in positions of authority. But it is possible to lead from positions of authority, and we need people in positions of authority to lead. It doesn’t naturally come with the territory, because people in authority are under enormous pressure to provide easy, quick, and decisive solutions to problems. They are under pressure to treat adaptive challenges as if they were technical.

There are a whole host of problems that maybe once were adaptive challenges to humanity, for which over time we evolved and developed capacity. That capacity to solve problems that are already within our knowhow, problems for which we have the solutions the right designs in place, are called by Ronald Heifetz, technical problems, but we could also call them routine problems. They are basically problems for which we have the knowhow. The difference between a technical problem and an adaptive challenge is the degree to which the adaptive challenge forces a response, requires, or demands a response, that is outside our current repertoire. Where our current knowhow isn’t sufficient. Where there isn’t an expert on the subject who can fix the problem. Where current organizational design or structure, stories, narratives, and metaphors, don’t do the job sufficiently. For example, a person has heart disease. You can redo the plumbing to their heart through very sophisticated surgery, but you still left afterwards with the problem of how to get the person to live a healthier life. Much easier to fix the heart than to change the heart and to get a person to stop smoking or to get better exercise. The compliance rates in surgery are around 20%. 80% of the time, even after life-threatening illness people have a great deal of difficulty changing the behaviours that are needed for them to do their part.

So, the authority structure can do its part, but adaptive challenges require people to do their part because in adaptive challenge you can’t take the problem off people’s shoulders and give them solutions. In an adaptive challenge the people are part of the problem and their ownership of the problem and their responsibility-taking for the problem becomes part of the solution itself.

Most problems come bundled. There are some problems that are purely technical. A child has an ear infection. The doctor prescribes some form of penicillin, and the child gets better. There are problems that are purely technical, but most problems that people in religious life and certainly in religious authority address are partly technical and partly adaptive they come bundled. One needs to be able to tease out those parts that can be treated with authoritative knowhow, and those parts that are going to require changes by the members.

There are a series of indicators to distinguish problems that are technical and those that are adaptive. For example, crises are usually an indicator of an adaptive challenge. A challenge that has been adaptive in the past that hasn’t been addressed properly and therefore resurfaces periodically, generates a crisis. The global economic crisis clearly represented a series of technical problems in terms of the design of regulation, of certain banking instruments and of lending practices, but also an adaptive challenge. A whole series of behaviours of everyday citizens, of high-powered finance executives, of politicians, as well as our basic philosophy of free-market-economics need to be adjusted. They need to be refashioned, in which a lot of experimentation is going to be required as we discover how we are going to build a healthy economy again. An economy that is not as vulnerable as we discovered we have. So, recurrent crisis is an indicator of an adaptive challenge.

Persistent conflict is an indicator of an adaptive challenge. One has to be able to probe, diagnose, and get an articulation of the nature of the conflict. What’s this conflict really about? How do I listen to what’s beneath the words? What are the real stakes, loyalties, constituencies, values, that are at the heart of this conflict?

An early indicator of an adaptive challenge is if you know quickly if it’s going to require people to learn new ways. If you know the current knowhow won’t do this, then you know right away that you’re dealing with an adaptive challenge and new learning is necessary.

“If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.” [12]

The classic and most common failure in leadership over many years is this diagnostic failure. People in positions of authority fail to lead because they have ended up treating an adaptive challenge as if it were a technical problem and they throw technical fixes at the problem. The problem persists and then over time members get disappointed that you haven’t really solved the problem and then they blame the leader, and you get pushed out, all the while the members keep hoping someone in authority is going to have a solution.

That pattern of dependency – members looking to authorities for decisive solutions – remains. So, you end up having a revolving door where people in leadership lose credibility, they keep over-promising what they can deliver, and members keep getting disappointed in what is delivered and blaming the leadership. And the dependency remains.

“When you blame others, you give up your power to change.” [13]

“Blame is simply the discharging of discomfort and pain. It has an inverse relationship with accountability. Blaming is a way that we discharge anger.” [14]

That cycle needs to be stopped by either members or people in authority calling for a different conversation. Calling members to realize that there are a lot of problems for which there are no quick technical solutions. Where their own responsibility-taking is going to be necessary. Where they’re going to have to pay some of the costs. Where some of their ways of being, their attitudes, their loyalties, will need to be re-negotiated. Where the job as an authority is not to provide the answers, but instead to frame the right questions, for which answers are developed and discovered over time by the collective intelligence of the people.

Leading an Adaptive Change

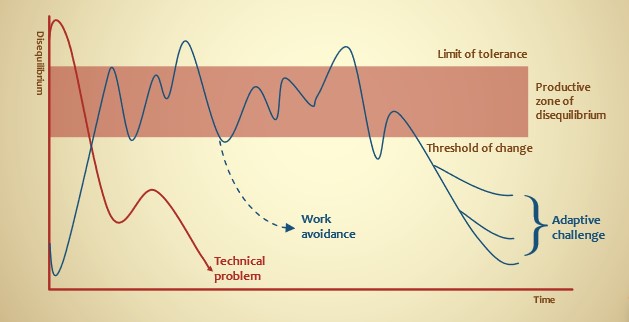

Heifetz talks about the experience of leading adaptive responses to an issue. He developed this graph exploring what he calls disequilibrium (stress, discomfort, dis-ease) over a period of change. He suggests that there is a productive zone of disequilibrium.

If the stress is greater than this zone, we reach the limit of our tolerance and experience panic, and our only priority is to reduce the stress. If the stress is less than this zone, we relax into thinking we don’t really need change – it seems too much effort. When stress rises the temptation is to immediately fix it and get back into the comfort zone. The challenge of leading an adaptive change is that we need to hold ourselves and our members in the zone of productive disequilibrium for a significant period of time – with the stresses rising and falling – until an adaptive solution emerges. What often emerges is not a single solution but two or three different responses which together change the situation fundamentally. Even when we work together to create the possibility of adaptive change, we can panic and settle for a half solution – which Heifetz suggests is avoiding the real work.

At the Korean Conference, we presented something similar with Otto Scharmer’s Theory U [15], in the light of Heart Spirituality [16]. Scharmer identifies the sort of responses that can be encountered as one tries to hold an organisation in this zone of productive disequilibrium. You may recall, the voice of judgement – “that’s not how we do it here!”, the voice of cynicism – “we say that’s our vision and values, but no-one takes them seriously.” And the voice of fear – “but we don’t know this will work.” These voices can block change, but if acknowledged with open mind, open heart and open will, they can enable “letting go” and “letting come” from within the zone of productive disequilibrium. We may also recognise this zone as the ‘U’ downward arc of co-sensing into co-presencing, the movements of encounter, intimacy and conversion of Heart Spirituality.

“We cannot change anything until we accept it. Condemnation does not liberate, it oppresses.” [17]

Tom Rivett-Carnac a political lobbyist for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change tells a story that helps illustrate the challenge of staying in the zone of productive disequilibrium or co-sensing. In the middle of a lengthy UN meeting, he was handed a note by colleague Christiana Figueres, the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework who had responsibility for the Paris Agreement. The note said, “Painful. But let’s approach with love!”

Rivett-Carnac felt for years that the climate crisis is the defining challenge of our generation, and he felt ready to play his part. But he realized all he could control were the day-to-day things of his own life, whereas what was going to determine climate issues were, “Will Russia wreck the negotiations?” “Will China take responsibility for their emissions?” “Will the US help poorer countries deal with their burden of climate change?” The differential felt so huge, he could see no way to bridge the two. It felt futile. When faced with an enormous challenge that we don’t feel we have any agency or control over, our mind will tell us, “Maybe it’s not that important. Maybe it’s not happening in the way that people say, anyway. There’s nothing that you individually can do, so why try?” But is it really true that humans will only take sustained and dedicated action on an issue of importance when they feel they have a high degree of control? Is our capacity to change really correlated to our level of control?

If we consider caregivers and nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, do we see people able to prevent the spread of the virus? Are they able to prevent patients dying? No, not always. Does that make their contribution futile and meaningless? Actually, it’s offensive even to suggest that. They show us that humans are capable of taking dedicated and sustained action, even when they can’t control the outcome.

In the Second World War, narrates Rivett-Carnac, London was under attack and the people of Britain would do anything to avoid facing the reality that Hitler would stop at nothing to conquer Europe. In the end, that reality broke through. Winston Churchill changed the story people told themselves about what they were doing and what was to come. Where previously there had been fear, there came a calm resolve, “a greatest hour”, “a country that would fight them on the beaches and in the hills and in the streets”, “a country that would never surrender”. It was simply a choice. A deep, stubborn form of optimism emerged, not avoiding the darkness that was pressing in but refusing to be cowed by it.

Stubborn optimism is powerful. It is not dependent on assuming that the outcome is going to be good or having a form of wishful thinking about the future. What it does is it animates action and infuses it with meaning. We saw it when Rosa Parks refused to get up from the bus. In Gandhi’s long salt marches and Nelson Mandela’s long march to freedom. And again, in the life-giving love of our MSC killed in Quiché, Guatemala.

“Be the change you wish to see in the world.” – Mahatma Gandhi

We, leaders and members, need to move beyond narratives of powerlessness. Stubborn optimism is a form of applied love – Spirituality of the Heart in action. It is both the world we want to create (“a new world emerging” [18]) and the way in which we can create that world. And this love is a choice for all of us. Yes, painful. But let’s approach with love!

“All changes, even the most longed for, have their melancholy; for what we leave behind us is a part of ourselves; we must die to one life before we can enter another.” [19]

Our core assumptions

In considering the dynamics of change in the light of the above thoughts, we might ask what are our core assumptions about change/transformation, about how adaptive challenges can be dealt with differently? Doing this helps leaders and members become ‘thinking people’ and not just compliant. It is essential to empower members, so they gain confidence to ask important questions, challenge unethical behaviour, take a proactive role in protecting our congregation from short-term thinking or potentially destructive behaviour, and to be inclusive.

Leaders need to have the power to influence, to develop, to enable people. This is fundamental to making things happen, and to do the job of a leader. However, the leader’s power is always a means to an end; the ‘end’ being the achievement of worthwhile outcomes for the greater good of all. So, how can I use my authority now as a leader, to enable post-conventional adaptive solutions that are in the service of the Mission? Equally, I might ask, in what ways might I use my authority to hinder the development of a project that could make a difference? Do I recognise when I am doing this? What contribution can we together make, to enable the members of our congregation, to embrace the mandate of the congregation and of this conference?

For a Synodal Church: communion, participation, and mission.

I conclude with an extract from the letter of João Braz Cardinal de Aviz (Prefect CICLSAL), to all members of consecrated life, dated June 24, 2021. He calls us to make our own Pope Francis’ invitation to set out on an ecclesial journey that begins this October and concludes in October 2023 with the celebration of the next Synod of Bishops on the theme “For a Synodal Church: communion, participation, and mission”. We are a part of this same journey of synodality in this cycle of General Conferences (2019 and 2021), and into the 2023 General Chapter.

Pope Francis reminds us: “A synodal Church is a Church which listens, which realizes; that listening ‘is more than simply hearing’. It is a mutual listening in which everyone has something to learn. The faithful people, the college of bishops, the Bishop of Rome: all listening to each other, and all listening to the Holy Spirit, the ‘Spirit of truth’ (Jn.14:17), in order to know what he ‘says to the Churches’ (Rev 2:7)”.

“It is precisely this path of synodality which God expects of the Church of the third millennium” because the world in which we live, and which we are called to love and serve, even with its contradictions, demands that the Church strengthen cooperation in all areas of her mission” (Address of Pope Francis at the Ceremony Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Institution of the Synod of Bishops, 17 October 2015).

These words strongly challenge the prophetic dimension of consecrated life, which finds its source in the sequela Christi, in communion with the Church and in the discernment that helps her to seek God’s will and to transform it into a life that can awaken the world!

No one should feel excluded from this ecclesial journey.

[1] The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. R.D. Laing. Penguin, August 1965.

[2] https://www.thedailybeast.com/elon-musk-of-tesla-motors-discusses-revenge-of-the-electric-car Elon Musk

[3] Pope Francis audience with the members of the 2017 MSC General Chapter, Rome.

[4] The Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis Evangelii Gaudium © 2013 Libreria Editrice Vaticana, #24.

[5] Homily Pope Francis Mass with cardinals in Rome. Pauline Chapel. Feast St. George, 23 April 2013.

[6] George Bernard Shaw, source of citation uncertain.

[7] Grubb Institute presentation, Immunity to Change. Francis Heery facilitation with GLT

[8] The Best of Sydney J. Harris. Sydney J. Harris

[9] Ron Heifetz interview in Creelman Research Vol 2.5 2009

[10] Jimmy Dean. American country music singer, television host, actor, and businessman.

[11] Video of Ronald Heifetz lecturing at Dukes Divinity School. ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfLLDvn0pI8 ).

[12] Where is Science Going? Max Planck. Literary Licensing, LLC, 2011

[13] 50 Ideas That Can Change Your Life. Robert Anthony. 1987, Berkley Press

[14] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZWf2_2L2v8 RSA Short: Blame, Brené Brown

[15] The Essentials of U Theory. C. Otto Scharmer. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018. P.27

[16] Spirituality of the Heart_ a Process-Oriented Approach. Chris Chaplin msc. 2019 General Conference, Korea.

[17] Modern Man in Search of a Soul. Carl G Jung. Mariner Books. 1955

[18] Jules Chevalier, 1900. Le Sacré-Coeur de Jesus. 1857 Ms. Archives, Rome.

[19] The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard. Anatole France. Mondial. France. 2007.